Gender Gap Report 21: India’s ranking continues to slide

The 2021 edition of the annual Global Gender Gap Report, produced by the World Economic Forum, was published recently. It examines gender gaps along four dimensions: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival and political empowerment.

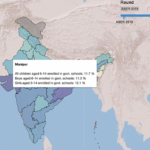

Of the 156 countries included this year, India is at the 17th position – from the bottom, i.e., at 140. In 2017, India ranked 108 among 144 countries, which was a slide of 20 points compared to 2016. Over the last six years, as the number of countries included in the report has increased, India’s relative position has worsened.

Like all indices, the “Global Gender Gap index”, first introduced in 2006, is a précis measure, in turn a combination of four different sub-indices (economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival and political empowerment), each summarizing multiple indicators. The index lies between 0 and 1, with 1 denoting complete parity. It is important to note that this index focuses on gender gaps, and not on whether “women are winning the battle of the sexes”, i.e. the focus is on the position of women relative to men (i.e. gender equality), rather than to their absolute position. The idea is to track changes in gender gaps both over time and across countries.

The WEF Gender Gap Rankings

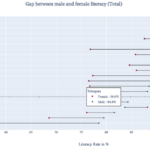

The CEDA team has developed a tracker which allows us to see the change in India’s position over time and relative to other countries separately for each of the sub-indices, as well as for the overall index. The lowest value of the index is 0 (far left) and the highest value is 1 (far right). We can hover over the graph to read the values for specific countries and use the slider on the left to examine the change over time.

Like all indices, it does not include everything that matters for gender equality, but focuses only on a few key measures. It should not be seen as a comprehensive treatise on gender equality, but as a useful pointer or a highlighter of key summary statistics that can be reliably measured and tracked.

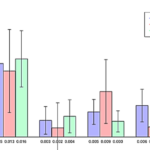

Of the four sub-indices, India’s rank (at 151 out of 156 countries) is very low in the economic participation and opportunity sub-index, where it is just one rank above Pakistan, and below Bangladesh and Saudi Arabia, but the value of the index is also low: 0.326.

We can see that India’s position, compared to other countries, in the economic participation and opportunity sub-index has consistently worsened since 2014. While 2020 was a difficult year for all countries due to the Covid-19 pandemic (reflected in the stalled or marginal progress on this component of the index globally), India’s downwards slide on this sub-component predates the pandemic. Globally, only 58.3% of this gap has closed, with no improvement over last year. In India, only 32.6% of this gap has closed (down from 44.8% in 2012).

The gender gap in economic participation and opportunity has widened by 12 percentage points since 2014.

This sub index is based on gender gaps in labour force participation, share in managerial positions, wage gaps, and wage parity (equal pay for equal work).

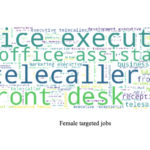

As the report states, globally, one of the most important reasons underlying gender inequality is women’s underrepresentation in the labour market. We need to note that the statistics included in the report are from 2019; in other words, these gaps do not reflect the widespread negative impact of Covid-19 on gender gaps in the labour market. The actual gaps in 2020 are likely to be higher.

As the CEDA tracker shows, it is important to focus on the value of the index as well as the ranking. For example, in the health and survival index, India’s value of 0.937 indicates the 93.7% of the gender gap has closed. However, India’s rank is at 155, followed by China because of the persistence of strong son preference and sex-selective abortions. Despite a reasonably good absolute value of the sub-index, India’s rank is low because other countries have done significantly better — 30 countries share the number one spot in this sub-index (with a value of 0.98).

India does relatively better in education (at 114 with a value of 0.962) reflecting the steady increase in women’s educational attainment and a steady closing of gender gaps.

Paradoxically, India’s rank on political participation index is surprisingly high at 51, despite the low value of 0.276, due to the low global value of this sub-index. This reflects the fact that while the rest of the world has made significant forward strides towards gender equality in the economic, educational and health spheres, the global progress on gender equality in political participation remains low.

Why Should Gender Equality Matter?

Discussions of gender gaps are often dismissed as issues that keep some academics, activists, NGO communities and development aid agencies – the liberal do-gooders – busy. What is significant about this particular ranking is that it is compiled by the World Economic Forum, which engages the “foremost political, business and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas.” Could this be because gender gaps matter for business and growth?

Indeed they do. It turns out that gender equality is desirable, even for purely instrumental reasons, and should be supported even by those who think of equity concerns as getting in the way of business. As several of the Global Gender Gap reports points out, talent is important for competitiveness and to find the best talent, everyone should have equal opportunity. “When women and girls are not integrated … the global community loses out on skills, ideas and perspectives that are critical for addressing global challenges and harnessing new opportunities.”

The 2021 report notes that at the current pace, it would take 195.4 years for the gender gaps to close in South Asia. While we aspire to be the Vishwaguru (teacher of the world), it appears that the rest of the world has something to teach us when it comes to basic elements of gender equality. Countries that do well on gender equality come in all shapes and sizes: countries at the very top include Iceland, Rwanda, Lithuania, Germany, Namibia, the Philippines, South Africa, in addition to the usual suspects from Scandinavia. India needs to pay urgent and focused attention to the massive gender gaps in the economic sphere, take immediate steps to increase work and livelihood opportunities for women, which will also contribute to a reduction on son preference and have positive effects on other indicators.

There is ample research documenting the staggering economic costs of side lining women. An OECD estimate reveals that gender-based discrimination in social institutions could cost up to USD 12 trillion for the global economy, and that a reduction in gender discrimination can increase the rate of growth of GDP. Internalization of this understanding would mean that gender equality has to be mainstreamed into economic policy making, rather than viewed as a residual concern to be tackled later, as an afterthought.

However, equality in the economic sphere can materialize only when we go beyond slogans to create a society that treats women as independent, intelligent, capable adults who are free to make their individual choices in all matters concerning their lives, and included as equals at all levels of decision-making.

(Note: an earlier version of this piece appeared as a comment in Economic and Political Weekly, Vol LVI, No. 15, April 10, 2021)