How many Indians live in a pucca house with basic amenities?

Less than a third of houses in India were pucca houses having a separate kitchen, a toilet, a bathroom with some arrangement for disposing of household waste in 2020-21.

Key Highlights

- Over one-fifth of rural houses were kutcha houses* in 2020-21, the shares being much larger in north-eastern states

- 16.3 percent of urban households lived in either a slum or a squatter settlement

- Over a third of houses in rural areas had no access to a bathing space, while one-fifth had no access to toilets

- Half of all households had no arrangements for disposing off household waste leading to households throwing away their garbage in an individual or a community spot

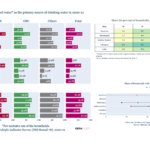

Only 28.4 percent of houses in India were pucca houses with a separate kitchen, a toilet, a bathroom and some arrangement for disposing of household waste in 2020-21. While 60.6 percent of urban houses satisfied these criteria, in rural areas this share was as low as 13.3 percent (Figure 1).

These are findings based on data from the Multiple Indicator Survey (NSS Round 78), 2020-21 released earlier this year. The survey was conducted between January 2020 and August 2021 with the aim of assessing the country’s progress on indicators relating to the Sustainable Development Goals. SDG 11.1 explicitly calls upon countries to “ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums”.

In this analysis, we explore access to basic household infrastructure in more detail.

Type of house

Eighty five percent of families in India lived in a pucca (permanent) house as of 2020-21, the data shows. Nearly all (96.7 percent) houses in urban areas were pucca houses, as compared to 79.5 percent of houses in rural areas. This is up from 66 percent of pucca houses in India in 2008-09 according to NSS 65th Round (55 percent in rural areas and 92 percent in urban areas).

A house is considered to be a “pucca house” if its walls and roofs are made of sturdy materials – timber, burnt bricks, stones, limestones, iron or metal sheets, cement or concrete. Kutcha houses, on the other hand, are those that use materials like grass, straw, reeds, bamboo, mud, unburnt brick, canvas and other kutcha material. A house is a pucca house in the NSS survey based on the material of the wall and roof used, and not of floors. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS) uses a stricter definition for a pucca house and includes the materials used for floors as well. According to the latest NFHS round (NFHS-5, 2019-21), 60.3 percent of households were pucca, while 34 percent were semi-pucca and 4.6 percent were kutcha in 2019-21.

In 2015, the Government of India launched the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, a flagship scheme to provide “Housing for All” by 2022. Under the rural vertical of the scheme (launched a year later), the beneficiaries registered as of June2023 (31.7 million) had exceeded the scheme’s target (29.3 million). While 22.8 million rural houses have been completed so far as per data on the website, completion rates** vary widely across states. Twelve states/UTs had completion rates lower than 50 percent, particularly those in the North-eastern region. Nagaland (12.4 percent), Sikkim (12.8 percent) and Meghalaya (18.9 percent) fared at the bottom among states in terms of completion of rural PMAY houses.

Figure 2

The findings of the NSS Round 78 corroborate this data. While several states had near universal presence of pucca houses in 2020-21, the same was not true for all parts of the country (Figure 2). In Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh and Tripura, only 43 percent of people were living in a pucca house in 2020-In Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh and Tripura, only 43 percent of houses were pucca in 2020-21. It is worth noting that the three states have a high share of tribal population, (ranging from 31.8 percent in Tripura to 68.8 percent in Arunachal Pradesh), a demographic group with relatively higher shares of households living in kutcha houses in 2020-21.

Over thirty eight percent of members of Scheduled Tribe (ST) communities lived in a kutcha house in 2020-21. Among those from Scheduled Caste (SC) communities, this share was 18.4 percent, while among those who belonged to an Other Backward Class (OBC) community, 12.1 percent were living in a kutcha house. The comparable share for those from other communities was 8.5 percent.

While urban areas do well in terms of having pucca houses, 16.3 percent of urban households lived in either slum or squatter settlements of which half lived in non-notified slums or squatters. Slums, as the survey defines them, are “poorly built tenements, mostly of temporary nature, crowded together, usually with inadequate sanitary and drinking water facilities in unhygienic conditions”.

Nagaland (44.9 percent of households) had the highest proportion of such households among all states and union territories (UTs), followed by Maharashtra (33.3 percent), Chhattisgarh (28.8 percent) and Bihar (27.8 percent). On the other hand, Chandigarh (0.4 percent) , Lakshadweep (0.4 percent) and Manipur (1.2 percent) had the lowest share of households living in slums (Figure 3).

Apart from lack of access to basic amenities, those living in slums have little to no tenurial security. A report by the Housing and Land Rights Network highlighted that 2 lakh persons were forcefully evicted from their homes in 2021, of which 14 percent were those living in slum areas. Among those facing an imminent threat of evictions, 34 percent were those living in slums. The threat of evictions also has perverse consequences on household’s employment decisions, with field reports (such as this, this and this) indicating that individuals may have to skip work to guard their homes when facing an imminent threat of demolition, and households often lose out on work and wages when they are forced to relocate far away after demolitions.

Kitchen

Across India, only 59 percent of houses had a separate kitchen.

According to survey definitions, a separate kitchen fulfills the criteria of having an exclusive room used for cooking purposes. This means that households cooking in the open, or sharing a kitchen with other households were counted as not having a separate kitchen.

Half of all rural households did not have a separate kitchen in their house in 2020-21. While another 37.4 percent of rural households did have a separate kitchen, they lacked a water connection inside the kitchen. This means that only 12.7 percent of rural households had an exclusive kitchen with a water connection in the country. The comparable figure for urban households having a kitchen with a water tap was 57.6 percent. Over a fifth (22 percent) of urban households did not have a separate kitchen, and another 20.4 percent did not have a water tap inside the kitchen.

Bathrooms and toilets

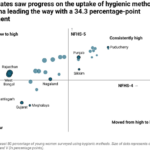

Sixty-three percent of houses had a separate bathroom across the country. This figure was only 55 percent for rural households as compared to 81.1 percent of urban households. In fact, 38.1 percent of rural households lacked any bathroom facilities at all, varying widely across states. Tripura (71.2 percent), Odisha (70.7 percent), and Jharkhand (68.6 percent) have the highest percentage of households that do not have access to bathrooms. Overall, five states in the country (Tripura, Odisha, Jharkhand, Bihar and Chhattisgarh) had more than half of all households reporting no bathroom facilities at all.

Figure 5

While the Swachh Bharat Mission focuses on access to toilets, access to bathrooms has been largely neglected in policy discussions. Lack of exclusive bathing spaces affect women and girls in particular, who have to compromise on hygiene, privacy, and convenience in order to bathe. Field studies (examples here and here) have highlighted the illnesses, harassment, discomfort and drudgery women experience because they have to bathe in the open.

The Swachh Bharat Mission – Rural had declared that all villages in the country were open defecation free on 2nd October 2019. However, multiple surveys since then have suggested otherwise. Fifteen percent of households in the country still lacked access to any toilet facility in 2020-21, varying between 21.3 percent in rural areas and 2.9 percent in urban areas, data from the NSS Round 78 shows. Another 12 percent had access to a common toilet (either shared by multiple households or public toilets). A higher proportion of urban households (16.3 percent) relied on common access toilets as compared to rural households (10 percent).

Garbage disposal

Across India, over half of all households had no arrangement to dispose of garbage. A third had a Municipal Corporation or Panchayat collect their waste. Consequently, most households in India either threw household waste in an individual dumping spot (30.6 percent), in a common dumping spot (28.2 percent) while another 7.4 percent threw garbage “anywhere”.

There was a stark rural-urban divide when it came to garbage disposal.

In 2020, the government notified the Plastic Waste Management Rules under the Swachh Bharat Mission – Rural putting the onus of rural solid waste management with the Gram Panchayats. As per the rules, the Gram Panchayats have to ensure door to door collection of waste that is segregated at source as well as its proper management and disposal.

However, a formal waste collection system was nearly entirely absent in rural India where the local Panchayats had made some arrangement to dispose of solid waste for only 17.9 percent of households, while another 9.1 percent of households had made their own arrangements in 2020-21, the NSS data shows. Sixty-nine percent of households had no arrangement at all for collection and disposal of waste. Among such households, 40.8 percent were simply disposing garbage in an individual spot of the household, while another 32.3 percent were disposing garbage in a common dumping spot shared by multiple households. The dumping spots could be an open area, street or drain according to the survey, or the households could be disposing off the waste by burning it.

In urban areas, on the other hand, Municipal Corporations had made some arrangement to collect and dispose of waste for 78.6 percent of houses, while 14.1 percent households had no institutional arrangements for collection of garbage.

In the absence of either a formal or an informal waste collection mechanism, households often resort to burning solid waste. A study by Pratham highlighted that a majority of rural households burnt plastic waste since single use plastics were not readily accepted by informal waste collectors who dominate the rural waste collection infrastructure. Chaudhary, P. et al. (2021) also estimate that the amount of waste being burned exceeds the amount being treated or landfilled in India. But burning solid waste, particularly plastics, is associated with serious health hazards from air pollution including cancer, respiratory diseases and heart disease among other things.

Notes

*Kutcha houses include both kutcha and semi-pucca houses.

**Completion rates are calculated as a percentage of Ministry of Rural Development’s targets in the state.

This is the final part in our series looking at household access to basic infrastructure and facilities based on data from the NSS Round 78. In Part I, we looked at access to piped drinking water, while Part II explored the use of clean fuel for cooking.

If you wish to republish this article or use an extract or chart, please read CEDA’s republishing guidelines.