The challenge of measuring and addressing hunger and malnutrition in India

The Global Hunger Index, an international tool developed to track hunger, has its flaws and limitations. So, what are some other data sources that measure hunger and malnutrition, and what do they show?

Key Highlights

- The Global Hunger Index has given India a score of 29.1 in its 2022 report, almost 11 points worse than the global average score of 18.2, putting it in the “serious” category of countries

- With the score India ranks 107 out of 121 countries, below most of its South Asian neighbours, except Afghanistan

- The index has been criticised for its conceptual framing and methodology of measuring hunger, triggering a debate on the scale of hunger in India and how best to measure it

- Even as large shares of the population benefit from the public distribution system, household surveys such as the NFHS and CNNS show that “hidden hunger” remains widespread

For the past couple of years, the release of the Global Hunger Index (GHI) has initiated charged discussions in India about the severity of the hunger crisis in the country and how best to measure it. But what is the index, why is there a debate, and what do we know about the hunger and nutrition challenge from other (domestic) data sources? Our data narrative explores some of these questions:

An index to measure and track hunger at the global level

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is an annual report published jointly by Concern WorldWide, an international humanitarian organisation, and Welthungerhilfe, a private aid organisation based in Germany. The index aims to “comprehensively measure and track hunger at the global, regional, and country levels”.

The index scores countries based on four indicators:

- Undernourishment (the share of the population with insufficient caloric intake)

- Child stunting (the share of children under age five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition)

- Child wasting (the share of children under age five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition)

- Child mortality (the share of children who die before their fifth birthday, partly reflecting the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments)

For the first, the GHI uses data from the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), and the other three data points come from other international organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), World Bank, Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), and United Nations Children Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Each of the component indicators is given a standardized score. This score is based on thresholds set slightly above the highest country-level values observed worldwide for that indicator since 1988. As the GHI explains this, if in a particular year, the prevalence of undernourishment in a country is 40 percent, its standardized undernourishment score will be 50. This indicates that the country is “approximately halfway between having no undernourishment and reaching the maximum observed level” since 1988.

These standardized scores for each component are then aggregated to calculate the GHI score for each country. Undernourishment and child mortality each contribute one-third of the GHI score, while child stunting and child wasting contribute one-sixth of the score. Countries get scored on a 100-point scale, with 0 representing no hunger/the best score, and 100 representing the worst score. While these scores allow inter-country comparisons, they are not comparable across years, but can only be compared to what are considered benchmark reference years.

As the index defines this, “a high GHI score can be evidence of a lack of food, a poor-quality diet, inadequate child caregiving practices, an unhealthy environment, or a combination of these factors.

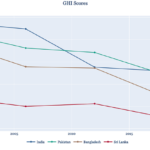

India scored 29.1 on the GHI for 2022, almost 11 points worse than the global average score of 18.2, putting it in the “serious” category of countries, and at the 107th rank among 121 countries scored on this year’s index. India’s score has improved considerably since 2000, when the index gave it 38.8, putting it in the “alarming” category. However, after much improvement, progress seems to have stagnated in recent years – the country’s hunger score worsened marginally between 2014 and 2022. It is now ranked below most of its South Asian neighbours, except for Afghanistan.

The debate

Since the past couple of years, the GHI scores have been met with strong methodological criticism in India. The Indian government has dismissed the index arguing that it was an “an erroneous measure of hunger and suffers from serious methodological issues”, going as far as to say that the index was an effort to “taint India’s image as a nation that does not fulfil the food security and nutritional requirements of its population”.

While some dismiss the government’s criticism, many experts too have been critical of the index’s methodology. Economist Abhijit Banerjee has, in the past, cautioned against the “model-based” methodology of the index. There are two broad critiques of the index.

First, experts have raised questions over the choice of indicators to measure “hunger” of the entire population since three of the four indicators are related to young children. Further, various studies show that, stunting, wasting and child mortality are not always a result of inadequate food, but symptomatic of the complex interplay of a range of factors. For example, in his research examining why children in India were shorter than children in Africa despite India being richer on average than Africans, economist Dean Spears (2020) points towards the critical role played by sanitation. The practice of open defecation can lead to infectious diseases such as diarrhoea which harm the nutrition of growing children, and of pregnant and breastfeeding mothers. Deshpande and Ramachadran (2022) point to the role of social institutions and practices such as caste hierarchy and stigma that result in lower caste children having higher rates of chronic malnutrition compared to upper caste children. CEDA has highlighted this issue last year through a data narrative and a Picture This entry.

Another study by Hong Nguyen et al (2020) found that children born to adolescent mothers were more likely to be underweight and stunted than children born to adult mothers. Children born to adolescent mothers were also less likely to get adequate diets, and adolescent mothers were themselves likely to be shorter and thinner. There has been research on the role of public infrastructure, and maternity support. Against such a backdrop, sociologist Sonalde Desai (2022) argues that while indicators of child health are related to poor food intake, “none of them is solely determined by hunger” and that a range of factors make a difference.

The other point of contention is related to the data source for the fourth indicator – the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) used to estimate the proportion of undernourished (PoU) population. The FIES is the tool used by the FAO to measure people’s experiences of food insecurity through eight questions. The survey was developed in 2013 to address the global data gap in measuring food insecurity, and the survey is conducted by Gallup World Poll. For India, a sample of 3,000 respondents was used to collect this data. The FIES has been critiqued for the small, unrepresentative sample and how it reports its findings.

So, how severe is the hunger and malnutrition challenge in India?

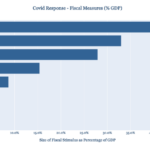

India, once witness to famines and starvation deaths, has come a long way in its journey to address hunger. With its massive public distribution system, and food made a right under the National Food Security Act in 2013, the Indian state has been providing basic cereals and grains to ensure that people do not go hungry, despite their economic situation. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the coverage was expanded and food made free, benefitting an estimated 810 million people in the country. However, technical glitches, leakages and bureaucratic processes can lead to some of the most vulnerable getting excluded from these benefits, a challenge that persists despite the admirable progress made.

While the state’s intervention may have helped alleviate starvation, an important question remains: is India’s population well nourished?

Household surveys provide some answer. While they don’t measure “hunger”, the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) and the Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey (CNNS) show that hidden hunger is widespread in the country.

Hidden hunger is a term used for micronutrient deficiencies – a form of undernutrition that “occurs when intake or absorption of vitamins and minerals is too low to sustain good health and development in children and normal physical and mental function in adults”.

This kind of deficiency does not produce hunger as we know it, observed a former deputy executive director of UNICEF, adding one “might not feel it in the belly, but it strikes at the core of your health and vitality.” Around 45% of deaths among children under 5 years of age are linked to undernutrition, the WHO estimates.

Anaemia is an indicator of both poor nutrition and poor health, says the World Health Organisation (WHO). The most common causes of anaemia include nutritional deficiencies, particularly iron deficiency, though deficiencies in folate, vitamins B12 and A are also important causes, it notes.

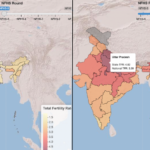

Anaemia is almost a norm in young children in India, data from the NFHS shows. Among children aged between 6 to 59 months, 67.1 percent were found to be anaemic, with 35.8 percent being moderately anaemic and 2.1 percent severely anaemic.

Among some age groups, even a higher share of babies was anaemic – 75.2 percent of all babies aged 6 to 8 months had some form of anaemia – among babies aged 9 to 11 months, 78.7 percent were anaemic, and among 12 to 17 months, the share was 80 percent. The prevalence remained high across socio-economic backgrounds, but babies whose mothers had no or little schooling, or those whose mothers were anaemic, and those from poorer households were even more likely to be anaemic.