Trends in youth employment in India: 2017-18 to 2022-23

Much has been said about India’s demographic dividend, but the high shares of unemployed youth, especially young women and those with higher levels of education merit urgent attention.

Key highlights

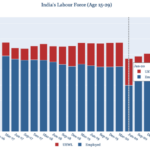

- As of 2022-23, only 42.1 percent of India’s youth (aged 15-29 years) were part of its labour force with this share being 61.6 percent for young men, and only 19.7 percent for young women

- Among those in the labour force, 13.2 percent were unemployed in 2022-23, with this share being higher for women, and for those with higher levels of education

- Young workers are most likely to be working in the service sector in urban areas, while in rural areas, agriculture continues to be the largest employment sector

- Less than a third of the youth was employed in regular/salaried jobs in 2022-23

- While there has been some improvement in the LFPR of young women, especially those living in rural areas, they continue to be predominantly occupied in the agriculture sector, and work as unpaid helpers

In its flagship report on global employment and social outlook for 2023, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) had raised its concern about the labour force participation of two demographic groups – women and the youth. Both tend to “fare significantly worse in labour markets, a fact indicative of large inequalities in the world of work in many countries”, the organisation noted.

This concern rings true in the Indian labour market too. The labour force participation rates (LFPR) of both groups is considerably lower, and young women fare the worst on this metric. Through several previous analyses, CEDA has dived into women’s LFPR (see here, here and here).

In this analysis, we explore patterns in the LFPR of the 15-29 age group (defined as the youth for the purpose of this analysis) between 2017-18 and 2022-23. All LFPR calculations are based on data from the Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFS), and refer to the current weekly status (CWS), where the reference period is one week. Note that LFPR numbers refer to the labour force, and thus include both the employed as well as unemployed.

Less than half of India’s youth was part of the labour force in 2022-23

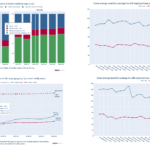

As of 2022-23, only 42.1 percent of India’s youth were part of its labour force with this share being 61.6 percent for young men, and only 19.7 percent for young women. This was lower than the labour force participation rates (LFPR) than the working age population (15-59 years) (Figure 1).

Between 2017-18 and 2022-23, the LFPR for both young men and women increased slightly, with this increase being greater in rural areas, and especially for rural women. In this period, the LFPR of the youth living in India increased from 38.2 percent to 41.2 percent. The LFPR for young women living in rural areas witnessed an increase of almost six percentage points from 14.1 percent during 2017-18 to 19.7 percent in 2022-23.

Among the youth living in urban areas, the LFPR saw a relatively smaller improvement – from 38.2 percent to 40 percent during the same period. It is worth noting that the LFPR of young men in urban areas has seen a marginal decline – from 58.4 percent in 2017-18 to 57.9 percent in 2022-23.

Within the youth, a further breakdown into age groups of 15-19, 20-24, 25-29 reveals great variations.

The LFPR among the 15-19 age group, when many are still part of the education system, is the lowest. In 2022-23, 22.7 percent of young men and 7.7 percent of young women of this age group were in the labour force. While the LFPR of young men aged 15-19 years has seen a small decline in both urban and rural India in the last six years, for young women in this cohort, especially those in rural areas, the LFPR has seen a small (3.7 percentage points) rise between 2017-18 and 2022-23.

The gender gap in the LFPR widens in the 20-29 years age group. This is the age when women are most likely to get married and have their first child (the median age of marriage for women aged 25-49 was 18.8 years, and the median age when the women in this age group had their first child was 21.2 years in 2019-21, data from the National Family Health Survey (Round 5) shows. Among men of the same age group, the median age of marriage was higher (24.9 years).

When it comes to the 20-24 years age group, 72.2 percent of men and 23.4 percent of women in this age group were part of the labour force in 2022-23. Within the 25-29 age group, the gender gap in the LFPR widens further. While the labour force participation is near universal for men, among women, this share varied from 27.6 percent in rural to 29.7 percent in urban areas in 2022-23.

The youth is most likely to be working in the services sector, but in rural areas, agriculture still dominates

The service sector was the major employer of the youth in the country in 2022-23 with a share of 32.7 percent, followed by agriculture, forestry, and fishing with a share of 32.4 percent. A fifth were working in the construction sector and the rest in manufacturing. When compared with the working age population, the share of young men working in the agriculture and service sector was lower. Young men were more likely to be engaged in the construction sector. Younger women, on the other hand, were more likely to be working in services and manufacturing as compared to their working-age counterparts (Figure 4).

For rural youth, agriculture continues to be the predominant occupational sector with 42.2 percent of those aged 15-29 still employed in the same. In the past six years, there has been a shift in young men moving from agriculture to construction, the share in agriculture declined by almost 8 percentage points and the share of employment in construction increased by more than 10 percentage points. But young women continue to be predominantly occupied in the primary sector with hardly any sectoral shifts (Figure 5).

Among their urban counterparts, services dominate, engaging 62.5 percent of the workforce as of 2022-23. The share of the urban youth workforce working in services has seen a small increase in recent years. On the other hand, 23.3 percent of young men and 23.4 percent of young women in urban areas were employed in the manufacturing sector in 2022-23, 3.4 and 0.4 percentage points lower than the share in 2017-18 respectively. The construction sector employed another 13.3 percent of young men, and only 2.1 percent of young women.

An increasing share of young women are self-employed, while the share of self-employed young men has seen a small decline in recent years

Only 27.5 percent of the young workers were in salaried jobs in 2022-23, with this share being lower in rural areas. The majority (45.3 percent) of India’s youth were self-employed with this share being higher for women and for those living in rural areas.

As is the case with the working age population, self-employment has been on the rise among the youth too in the period between 2017-18 and 2022-23 (Figure 6).

However, the share of workforce working as unpaid helpers is much higher in the youth (24.4 percent) as compared to the working age group (15.8 percent). This is largely due to the higher share of younger men working as unpaid helpers (20.6 percent) as compared to men in the working age (8.9 percent). Among women, the share of those working as unpaid helpers is high across age groups. (37 percent in the youth and 32.7 percent in the working-age group).

The share of the youth in casual labour, 26.7 percent, remained more than the share of the working age population in casual labour, 21.9 percent. Young men are more likely to be employed in casual labour, 31 percent, as compared to the young women, 12.5 percent. Across sectors, the share of casual labour workers was more for the rural youth, 31.5 percent, than the urban youth, 12.5 percent.

The distribution of youth workers across sectors varied widely. During 2022-23, the agriculture sector had the highest share of self-employed youth, 79.8 percent, followed by manufacturing, 39.4 percent, and the service sector, 37.8 percent. Of the self-employed youth in agriculture, almost three-fourth were employed as unpaid helpers indicating high rates of disguised employment in this sector. On the other hand, both the manufacturing and the service sector had almost two-third of the self-employed youth working as own account workers, who operate their enterprises on their own account or with one or a few partners and who during the reference period by and large, run their enterprise without hiring any labour.

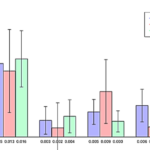

The urban, salaried youth earns the most, while self-employed women have the lowest earnings

On average, the youth working in salaried employment earned INR 14,709 per month in 2022-23, with urban youth earning more than their rural counterparts. In comparison, the average gross monthly earnings for self-employed youth workers was lower at INR 10,749 in 2022-23, with an even wider gap between for rural and urban youth. The average daily wage for the youth working in non-public casual work in 2022-23 was INR 406 per day.

Young women workers earned less than their male counterparts, with this gap being the widest among self-employed persons. As CEDA has noted in a previous analysis, earnings for those self-employed only include those who are employers and own-account workers, and exclude unpaid helpers. Given the high shares of young women working as unpaid helpers, if the latter were to be included in the calculations, the average earnings would be much lower, and the gender-gap much wider. In contrast, among salaried workers, the average monthly earnings for women were higher than for men. This was largely on the account of salaried women in urban areas earning the most among young workers on average (Figure 7).

Unemployment among the youth remains high, especially for young women living in urban areas as well as those with higher levels of education

Not everyone who is part of the labour force is engaged in employment. The labour force comprises of both the employed and those who are looking for work but are not able to get it i.e. the unemployed.

Among the 42.1 percent youth who were in the labour force in 2022-23, 13.2 percent were unemployed in 2022-23. This was more than double the share of those who were unemployed in the working age population in the same period (5.4 percent).

For years, India has grappled with the challenges of job creation, especially for the youth. But India is not an exception – as the ILO observed in its report, the youth in the labour force is much more likely than adults to be unemployed.

On an encouraging note, the share of the youth that are unemployed has witnessed a notable decline in recent years. However, unemployment continues to be a serious concern among the youth, with the unemployment rate being the highest for young women living in urban areas, the PLFS data shows.

Between 2017-18 and 2022-23, the share of youth who were unemployed declined significantly from 21.4 percent during 2017-18 to 13.4 percent in 2022-23. This decline in unemployment was driven by rural India where the share of those who were unemployed decreased from 20.9 percent to 11.4 percent in this period. In the same period, the share of urban youth who were unemployed decreased from 22.7 percent to 18.4 percent.

Young women, especially those living in urban areas, had the highest shares of unemployed among the youth. In 2022-23, nearly a quarter (23.8 percent) of young women living in urban areas who were looking for work were unemployed, as compared to 16.4 percent of their male peers, and 11 percent of rural women. When this is read with the fact that young women living in urban areas are most likely to be working in salaried jobs (Figure 6), it is an indication that the availability of quality jobs matters for women’s employment.

Despite the recent decline, unemployment continues to be significantly higher among youth who have attained higher levels of education. This could be both due to a lack of quality of jobs, and/or higher frictional unemployment in this cohort. Over a third (33.8 percent) of the youth who had more than 15 years of formal education and who were looking for work were unemployed in 2022-23, with this being higher for women (38 percent) as compared to men (31.3 percent). In contrast, the corresponding share of unemployed among those with no formal education and who were in the labour force was 4.5 percent (Figure 8a).

| Years of Education | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Formal Education | 11.1 | 12.7 | 11.0 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 4.5 |

| 1-5 Years | 12.3 | 11.8 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 7.5 | 3.6 |

| 6-10 Years | 17.1 | 16.4 | 15.3 | 12.7 | 11.8 | 8.0 |

| 11-15 Years | 29.8 | 29.2 | 27.9 | 24.5 | 23.4 | 19.6 |

| More than 15 Years | 39.9 | 38.4 | 37.7 | 36.4 | 32.1 | 33.8 |

| Total | 21.4 | 21.5 | 20.7 | 18.1 | 17.0 | 13.2 |

Numbers reflect percentages and years indicate years of education.

Source: Unit level data, Periodic Labour Force Survey

| Sex | Years of Education | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | No Formal Education | 14.3 | 16.1 | 14.3 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 6.2 |

| Women | No Formal Education | 3.9 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| Men | 1-5 Years | 13.8 | 12.7 | 12.4 | 12.1 | 8.9 | 3.7 |

| Women | 1-5 Years | 6.0 | 8.0 | 6.6 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| Men | 6-10 Years | 17.9 | 17.2 | 16.5 | 13.9 | 13.0 | 9.2 |

| Women | 6-10 Years | 12.3 | 11.4 | 9.7 | 7.0 | 5.6 | 3.6 |

| Men | 11-15 Years | 28.0 | 27.3 | 27.5 | 23.3 | 22.4 | 18.2 |

| Women | 11-15 Years | 37.7 | 37.4 | 29.7 | 28.9 | 27.2 | 24.4 |

| Men | More than 15 Years | 37.0 | 35.8 | 35.1 | 32.2 | 29.7 | 31.3 |

| Women | More than 15 Years | 45.3 | 43.8 | 41.9 | 44.0 | 36.5 | 38.0 |

| Men | Total | 21.3 | 21.1 | 20.9 | 18.0 | 17.0 | 12.8 |

| Women | Total | 22.1 | 23.3 | 19.8 | 18.6 | 16.9 | 14.4 |

Numbers reflect percentages and years indicate years of education.

Source: Unit level data, Periodic Labour Force Survey

Every now and then, news articles (see some recent examples here, here, here, here and here) reporting lakhs of jobs applications received for a handful of jobs – often in the public sector — catches national attention. These disparate incidents reflect the extreme gap between the high demand (and limited supply) for quality jobs among India’s youth. Much has been said about India’s demographic dividend, but the high shares of those working as unpaid helpers, and high proportion of unemployed among the youth in the labour force, especially young women and for those with higher levels of education merit urgent attention.

If you wish to republish this article or use an extract or chart, please read CEDA’s republishing guidelines.